written by SARAH BOXER

NOVEMBER 2015 ISSUE

The Atlantic

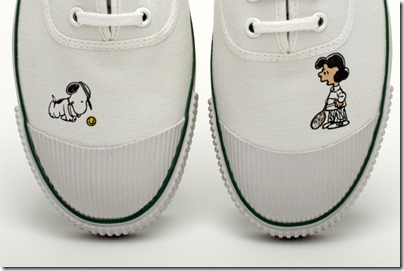

Some of Charles Schulz’s fans blame

the cartoon dog for ruining Peanuts.

Here’s why they’re wrong.

It really was a dark and stormy night.

On February 12, 2000,

Charles Schulz—who had single-handedly

drawn some 18,000 Peanuts comic strips,

who refused to use assistants to

ink or letter his comics,

who vowed that after he quit,

no new Peanuts strips would be made—

died, taking to the grave, it seemed,

any further adventures of the gang.

Hours later,

his last Sunday strip came out

with a farewell:

“Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy …

How can I ever forget them.”

By then, Peanuts was carried by

more than 2,600 newspapers in

75 countries and read by

some 300 million people.

It had been going for five decades.

Robert Thompson,

a scholar of popular culture,

called it “arguably the longest story told by

a single artist in human history.”

The arrival of The Peanuts Movie this fall

breathes new life into the phrase

over my dead body—

starting with the movie’s title.

Schulz hated and resented the name Peanuts,

which was foisted on him by

United Feature Syndicate.

He avoided using it:

“If someone asks me what I do,

I always say,

‘I draw that comic strip with

Snoopy in it, Charlie Brown and his dog.’ ”

And unlike the classic Peanuts television specials,

which were done in a style

Schulz approvingly called “semi-animation,”

where the characters flip around

rather than turning smoothly in space,

The Peanuts Movie

(written by Schulz’s son Craig and

grandson Bryan, along with

Bryan’s writing partner, Cornelius Uliano)

is a computer-generated 3-D-animated feature.

What’s more,

the Little Red-Haired Girl,

Charlie Brown’s unrequited crush,

whom Schulz promised never to draw,

is supposed to make a grand appearance.

AAUGH!!!

The characters could stir up

shockingly heated arguments over

how to be a decent human being

in a bitter world.

Before all that happens,

before the next generation gets

a warped view of what Peanuts is and was,

let’s go back in time.

Why was this comic strip so

wildly popular for half a century?

How did Schulz’s cute and lovable characters

(they’re almost always referred to that way)

hold sway over so many people—

everyone from

Ronald Reagan to Whoopi Goldberg?

Peanuts was deceptive.

It looked like kid stuff, but it wasn’t.

The strip’s cozy suburban conviviality,

its warm fuzziness, actually

conveyed some uncomfortable truths

about the loneliness of social existence.

The characters, though funny,

could stir up shockingly heated arguments over

how to survive and still be a

decent human being in a bitter world.

Who was better at it—

Charlie Brown or Snoopy?

The time is ripe to see what was

really happening on the pages of Peanuts

during all those years.

Since 2004,

the comics publisher Fantagraphics

has been issuing The Complete Peanuts,

both Sunday and daily strips,

in books that each cover two years and

include an appreciation from a notable fan.

(The 25-volume series will be

completed next year.)

To read them straight through,

alongside David Michaelis’s

trenchant 2007 biography,

Schulz and Peanuts,

is to watch the characters evolve from

undifferentiated little cusses into

great social types.

In the stone age of Peanuts—

when only seven newspapers carried the strip,

when Snoopy was still an

itinerant four-legged creature with

no owner or doghouse,

when Lucy and Linus had yet to be born—

Peanuts was surprisingly dark.

The first strip,

published on October 2, 1950,

shows two children, a boy and a girl,

sitting on the sidewalk.

The boy, Shermy, says,

“Well! Here comes ol’ Charlie Brown!

Good ol’ Charlie Brown …

Yes, sir! Good ol’ Charlie Brown.”

When Charlie Brown is out of sight,

Shermy adds, “How I hate him!”

In the second Peanuts strip

the girl, Patty, walks alone, chanting,

“Little girls are made of sugar and spice …

and everything nice.”

As Charlie Brown comes into view,

she slugs him and says,

“That’s what little girls are made of!”

Although key characters were missing or

quite different from what they came to be,

the Hobbesian ideas about society that

made Peanuts were already evident:

People, especially children,

are selfish and cruel to one another;

social life is perpetual conflict;

solitude is the only peaceful harbor;

one’s deepest wishes will

invariably be derailed and

one’s comforts whisked away;

and an unbridgeable gulf yawns between

one’s fantasies about oneself and

what others see.

These bleak themes, which

went against the tide of the go-go 1950s,

floated freely on the pages of Peanuts at first,

landing lightly on one kid or another until

slowly each theme came to be embedded in

a certain individual—

particularly Lucy, Schroeder, Charlie Brown,

Linus, and Snoopy.

In other words, in the beginning

all the Peanuts kids were,

as Al Capp,

the creator of Li’l Abner, observed,

“good mean little bastards

eager to hurt each other.”

What came to be Lucy’s inimitable

brand of bullying was suffused throughout

the Peanuts population.

Even Charlie Brown was a bit of a heel.

In 1951, for example,

after watching Patty fall off

a curb into some mud,

he smirks: “Right in the mud, eh?

It’s a good thing I was carrying the ice cream!”

Many early Peanuts fans—

and this may come as a shock to

later fans raised on the sweet milk of

Happiness Is a Warm Puppy—

were attracted to the strip’s

decidedly unsweet view of society.

Matt Groening, the creator of the strip

Life in Hell and The Simpsons, remembers,

“I was excited by the casual cruelty and

offhand humiliations at the heart of the strip.”

Garry Trudeau, of Doonesbury fame,

saw Peanuts as “the first Beat strip” because

it “vibrated with ’50s alienation.”

And the editors of Charlie Mensuel,

a raunchy precursor to

the even raunchier Charlie Hebdo,

so admired the existential angst

of the strip that

they named both publications after

its lead character.

At the center of this world was

Charlie Brown,

a new kind of epic hero—

a loser who would lie in the dark

recalling his defeats,

charting his worries,

planning his comebacks.

One of his best-known lines was

“My anxieties have anxieties.”

Although he was the glue holding together

the Peanuts crew (and its baseball team),

he was also the undisputed butt of the strip.

His mailbox was almost always empty.

His dog often snubbed him,

at least until suppertime,

and the football was always

yanked away from him.

The cartoonist Tom Tomorrow

calls him a Sisyphus.

Frustration was his lot.

When Schulz was asked whether

for his final strip he would let

Charlie Brown make contact with the football,

he reportedly replied,

“Oh, no! Definitely not! …

That would be a terrible disservice to him

after nearly half a century.”

For many fans,

there was something fundamentally rotten

about the new Snoopy.

Although Schulz denied any

strict identification with Charlie Brown

(who was actually named for one of

Schulz’s friends at the

correspondence school in Minneapolis where

Schulz learned and taught drawing),

many readers assumed they were

one and the same.

More important for the strip’s success,

readers saw themselves in Charlie Brown,

even if they didn’t want to.

“I aspired to Linus-ness;

to be wise and kind and highly skilled at

making gigantic structures out of playing cards,”

the children’s-book author Mo Willems

notes in one of the essays in

the Fantagraphics series.

But, he continues,

“I knew, deep down, that

I was Charlie Brown.

I suspect we all did.”

Well, I didn’t.

And luckily, beginning in 1952

(after Schulz moved from his hometown,

St. Paul, Minnesota,

to Colorado Springs for a year with

his first wife, Joyce, and her daughter, Meredith),

there were plenty more

alter egos to choose from.

That was the year the Van Pelts were born.

Lucy, the fussbudget, who was based

at first on young Meredith,

came in March.

Lucy’s blanket-carrying little brother,

Linus, Schulz’s favorite character to draw

(he would start with his pen

at the back of the neck),

arrived only months later.

And then, of course,

there was Snoopy,

who had been around from the outset

(Schulz had intended to name him Sniffy) and

was fast evolving into an articulate being.

His first detailed expression of consciousness,

recorded in a thought balloon,

came in response to Charlie Brown

making fun of his ears:

“Kind of warm out today for

ear muffs, isn’t it?”

Snoopy sniffs:

“Why do I have to suffer such indignities!?”

I like to think that Peanuts and identity politics

grew up together in America.

By 1960, the main characters—

Charlie Brown, Linus, Schroeder, Snoopy—

had their roles and their acolytes.

Even Lucy had her fans.

The filmmaker John Waters,

writing an introduction to

one of the Fantagraphics volumes, gushes:

I like Lucy’s politics (“I know everything!” …),

her manners (“Get out of my way!” …),

her narcissism …

and especially her verbal abuse rants …

Lucy’s “total warfare frown” …

is just as iconic to me as

Mona Lisa’s smirk.

Finding one’s identity in the strip was like

finding one’s political party or

ethnic group or niche in the family.

It was a big part of the appeal of Peanuts.

Every character was a powerful personality with

quirky attractions and profound faults,

and every character, like some saint or hero,

had at least one key prop or attribute.

Charlie Brown had his tangled kite,

Schroeder his toy piano,

Linus his flannel blanket,

Lucy her “Psychiatric Help” booth,

and Snoopy his doghouse.

In this blessedly solid world,

each character came to be linked

not only to certain objects but

to certain kinds of interactions, too,

much like the main players in Krazy Kat,

one of the strips that Schulz admired and

hoped to match.

But unlike Krazy Kat, which was built upon

a tragically repetitive love triangle that

involved animals hurling bricks,

Peanuts was a drama of social coping,

outwardly simple but

actually quite complex.

Charlie Brown,

whose very character depended on

his wishes being stymied, developed

what the actor Alec Baldwin,

in one of the Fantagraphics introductions,

calls a kind of

“trudging, Jimmy Stewart–like

decency and predictability.”

The Charlie Brown way was to

keep on keeping on,

standing with a tangled kite or

a losing baseball team day after day.

Michaelis, Schulz’s biographer,

locates the essence of

Charlie Brown—and Peanuts itself—

in a 1954 strip in which

Charlie Brown visits Shermy and watches as

he “plays with a model train set whose

tracks and junctions and crossings spread …

elaborately far and wide in

Shermy’s family’s living room.”

After a while,

Charlie Brown pulls on his coat

and walks home … [and]

sits down at his railroad:

a single, closed circle of track …

Here was the moment when

Charlie Brown became a national symbol,

the Everyman who survives life’s

slings and arrows simply by

surviving himself.

In fact, all of the characters were survivors.

They just had different strategies for survival,

none of which was exactly pro-social.

Linus knew that he could

take his blows philosophically—

he was often seen, elbows on the wall,

calmly chatting with Charlie Brown—

as long as he had his security blanket nearby.

He also knew that if he didn’t have his blanket,

he would freak out.

(In 1955 the child psychiatrist D. W. Winnicott

asked for permission to use

Linus’s blanket as an illustration of

a “transitional object.”)

Lucy, dishing out

bad and unsympathetic advice

fromher “Psychiatric Help” booth,

was the picture of bluster.

On March 27, 1959,

Charlie Brown, the first patient to

visit her booth, says to Lucy,

“I have deep feelings of depression …

What can I do about this?”

Lucy replies:

“Snap out of it! Five cents, please.”

That pretty much sums up the Lucy way.

Schroeder at his piano

represented artistic retreat—

ignoring the world to pursue one’s dream.

And Snoopy’s coping philosophy was,

in a sense, even

more antisocial than Schroeder’s.

Snoopy figured that since no one will

ever see you the way you see yourself,

you might as well

build your world around fantasy,

create the person you want to be,

and live it out, live it up.

Part of Snoopy’s Walter Mitty–esque charm

lay in his implicit rejection of

society’s view of him.

Most of the kids saw him as just a dog,

but he knew he was way more than that.

Those characters who could not

be summed up with both

a social strategy and a recognizable attribute

(Pig-Pen, for instance,

had an attribute—dirt—

but no social strategy)

became bit players or fell by the wayside.

Shermy, the character who uttered the

bitter opening lines of Peanuts in 1950,

became just another bland boy by the 1960s.

Violet, the character who

made endless mud pies,

withheld countless invitations,

and had the distinction of being

the first person to

pull the football away from Charlie Brown,

was mercilessly demoted to

just another snobby mean girl.

Patty, one of the early stars,

had her name recycled for another,

more complicated character,

Peppermint Patty,

the narcoleptic tomboy who

made her first appearance in 1966 and

became a regular in the 1970s.

(Her social gambit was to fall asleep,

usually at her school desk.)

One of Charlie Brown’s best-known lines was

“My anxieties have anxieties.”

Once the main cast was set,

the iterations of their daily interplay were

almost unlimited.

“A cartoonist,” Schulz once said,

“is someone who has to

draw the same thing every day without

repeating himself.”

It was this

“infinitely shifting repetition of the patterns,”

Umberto Eco wrote in

The New York Review of Books in 1985,

that gave the strip its epic quality.

Watching the permutations of

every character working out

how to get along with

every other character demanded

“from the reader a continuous act of empathy.”

For a strip that depended on

the reader’s empathy,

Peanuts often involved dramas that

displayed a shocking lack of empathy.

And in many of those dramas,

the pivotal figure was

Lucy, the fussbudget who

couldn’t exist without others to fuss at.

She was so strident, Michaelis reports,

that Schulz relied on certain pen nibs for her.

(When Lucy was “doing some loud shouting,”

as Schulz put it, he would ink up a B-5 pen,

which made heavy, flat, rough lines.

For “maximum screams,”

he would get out the B-3.)

Lucy was, in essence, society itself,

or at least society as Schulz saw it.

“Her aggressiveness

threw the others off balance,”

Michaelis writes, prompting each character to

cope or withdraw in his or her own way.

Charlie Brown, for instance,

responded to her with incredible credulity,

coming to her time and again for

pointless advice or for football kicking.

Linus always seemed to approach her with

a combination of terror and equanimity.

In one of my favorite strips,

he takes refuge from

his sister in the kitchen and,

when Lucy tracks him down,

addresses her pointedly:

“Am I buttering too loud for you?”

It was Lucy’s dealings with Schroeder that

struck closest to home for Schulz,

whose first marriage, to Joyce,

began to fall apart in the 1960s while

they were building up their

huge estate in Sebastopol, California.

Just as Schulz’s retreat into his comic-strip world

antagonized Joyce, Michaelis observes,

so Schroeder’s devotion to his piano was

“an affront to Lucy.”

At one point,

Lucy becomes so fed up at her inability to

distract Schroeder from his music that

she hurls his piano into the sewer:

“It’s woman against piano!

Woman is winning!!

Woman is winning!!!”

When Schroeder shouts at her in disbelief,

“You threw my piano down the sewer!!,”

Lucy corrects him:

“Not your piano, Sweetie …

My competition!”

Now, that’s a relationship!

In this deeply dystopic strip,

there was only one character who could—

and some say finally did—

tear the highly entertaining, disturbed

social world to shreds.

And that happens to be

my favorite character,

Snoopy.

Before Snoopy had his signature doghouse,

he was an emotional creature.

Although he didn’t speak

(he expressed himself in thought balloons),

he was very connected to

all the other characters.

In one 1958 strip, for instance,

Linus and Charlie Brown are

talking in the background,

and Snoopy comes dancing by.

Linus says to Charlie Brown,

“My gramma says that

we live in a veil of tears.”

Charlie Brown answers:

“She’s right … This is a sad world.”

Snoopy still goes on dancing.

By the third frame, though,

when Charlie Brown says,

“This is a world filled with sorrow,”

Snoopy’s dance slows and

his face begins to fall.

By the last frame,

he is down on the ground—

far more devastated than

Linus or Charlie Brown, who are

shown chatting off in the distance,

“Sorrow, sadness and despair …

grief, agony and woe …”

But by the late 1960s,

Snoopy had begun to change.

For example,

in a strip dated May 1, 1969,

he’s dancing by himself:

“This is my ‘First Day of May’ dance.

It differs only slightly from

my ‘First Day of Fall’ dance,

which differs also only slightly from

my ‘First Day of Spring’ dance.”

Snoopy continues dancing and ends with:

“Actually, even I have a hard time

telling them apart.”

Snoopy was still hilarious,

but something fundamental had shifted.

He didn’t need any of the other characters

in order to be what he was.

He needed only his imagination.

More and more often

he appeared alone on his doghouse,

sleeping or typing a novel or a love letter.

Indeed, his doghouse—

which was hardly taller than

a beagle yet big enough inside to

hold an Andrew Wyeth painting

as well as a pool table—

came to be the objective correlative of

Snoopy’s rich inner life,

a place that no human ever got to see.

Some thought

this new Snoopy was an excellent thing,

indeed the key to the strip’s greatness.

Schulz was among them:

“I don’t know how he got to walking,

and I don’t know how he first began to think,

but that was probably one of the

best things that I ever did.”

The novelist Jonathan Franzen

is another Snoopy fan.

Snoopy, as Franzen has noted, is

the protean trickster whose freedom is

founded on his confidence that

he’s lovable at heart,

the quick-change artist who,

for the sheer joy of it,

can become a helicopter or

a hockey player or Head Beagle and

then again, in a flash,

before his virtuosity has a chance to

alienate you or diminish you,

be the eager little dog who

just wants dinner.

But some people detested the new Snoopy and

blamed him for what they viewed as

the decline of Peanuts

in the second half of its 50-year run.

“It’s tough to fix the exact date when

Snoopy went from being the strip’s

besetting artistic weakness to

ruining it altogether,”

the journalist and critic

Christopher Caldwell wrote in 2000,

a month before Schulz died, in an essay

in New York Press titled “Against Snoopy.”

But certainly by the 1970s, Caldwell wrote,

Snoopy had begun wrecking

the delicate world that Schulz had built.

The problem, as Caldwell saw it, was that

Snoopy was never a full participant in

the tangle of relationships that

drove Peanuts in its Golden Age.

He couldn’t be:

he doesn’t talk … and

therefore he doesn’t interact.

He’s there to be looked at.

Snoopy unquestionably took the strip to

a new realm beginning in the late 1960s.

The turning point, I think,

was the airing of

It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown

in 1966.

In this Halloween television special,

Snoopy is shown sitting atop his doghouse

living out his extended fantasy of

being a World War I flying ace

shot down by the Red Baron and then

crawling alone behind enemy lines in France.

Snoopy is front and center for six minutes,

about one-quarter of the whole program,

and he steals the show,

proving that he doesn’t need the

complicated world of Peanuts to thrive.

He can go it alone.

And after that he often did.

In 1968, Snoopy became NASA’s mascot.

The next year, Snoopy had a

lunar module named after him for

the Apollo 10 mission

(the command module was called Charlie Brown).

In 1968 and 1972,

Snoopy was a write-in candidate for

president of the United States.

Plush stuffed Snoopys became popular.

(I had one.)

By 1975,

Snoopy had replaced Charlie Brown as

the center of the strip.

He cut a swath through the world.

For instance,

in parts of Europe Peanuts came

to be licensed as Snoopy.

And in Tokyo,

the floor of the vast toy store Kiddy Land that is

devoted to Peanuts is called Snoopy Town.

To accommodate this new Snoopy-centric world,

Schulz began making changes.

He invented a whole new

animal world for Snoopy.

First came Woodstock, a

bird who communicates only with Snoopy

(in little tic marks).

And then Snoopy acquired a family:

Spike, a droopy-eyed, mustachioed beagle,

followed by Olaf, Andy, Marbles, and Belle.

In 1987, Schulz acknowledged that

introducing Snoopy’s relatives had been a blunder,

much as Eugene the Jeep had been

an unwelcome intrusion into

the comic strip Popeye:

It’s possible—I think—

to make a mistake in the strip and

without realizing it, destroy it …

I realized it myself a couple of years ago

when I began to introduce

Snoopy’s brothers and sisters …

It destroyed the relationship that

Snoopy has with the kids,

which is a very strange relationship.

He was right.

Snoopy’s initial interactions with the kids—

his understanding of humanity,

indeed his deep empathy

(just what they were often missing),

coupled with his

inability to speak—were unique.

And that’s why

whenever Snoopy’s relatives showed up,

the air just went out of the strip.

But for many fans,

it wasn’t merely Snoopy’s brothers and sisters

dragging him down.

There was something fundamentally rotten

about the new Snoopy,

whose charm was based on

his total lack of concern about

what others thought of him.

His confidence, his breezy sense that

the world may be falling apart but

one can still dance on,

was worse than irritating.

It was morally bankrupt.

As the writer Daniel Mendelsohn

put it in a piece in

The New York Times Book Review,

Snoopy “represents the part of ourselves—

the smugness, the avidity, the pomposity,

the rank egotism—

most of us know we have but try to

keep decently hidden away.”

While Charlie Brown was made to

be buffeted by other personalities and

cared very much what others thought of him,

Snoopy’s soul is all about self-invention—

which can be seen as delusional self-love.

This new Snoopy,

his detractors felt,

had no room for empathy.

To his critics, part of

what’s appalling about Snoopy is

the idea that it’s possible to

create any self-image one wants—

in particular, the profile of someone with

tons of friends and accomplishments—

and sell that image to the world.

Such self-flattery is

not only shallow but wrong.

Snoopy, viewed this way,

is the very essence of selfie culture,

of Facebook culture.

He’s the kind of creature who

would travel the world only in order to

take his own picture and

share it with everyone,

to enhance his social image.

He’s a braggart.

Unlike Charlie Brown, who is alienated

(and knows he’s alienated),

Snoopy is alienating

(and totally fails to recognize it).

He believes that he is what

he’s been selling to the world.

Snoopy is “so self-involved,”

Mendelsohn writes,

“he doesn’t even realize he’s not human.”

Just as some people thought that

Charlie Brown, the insecure loser,

the boy who never won the love of

the Little Red-Haired Girl,

was the alter ego of Schulz himself

near the beginning of his career,

so Snoopy could be cast as

the egotistical alter ego of

Schulz the world-famous millionaire,

who finally found a little happiness in

his second marriage and thus

became insufferably cutesy.

(In 1973,

Schulz and his wife divorced,

and a month later

Schulz married Jeannie Clyde,

a woman he met at the Warm Puppy Café,

at his skating rink in Santa Rosa, California.)

Two-legged Snoopy,

with his airs and fantasies—

peerless Snoopy,

rich Snoopy,

popular Snoopy,

world-famous Snoopy,

contented Snoopy—

spoiled it all.

Schulz, who had a lifelong fear of

being seen as ostentatious, believed that t

he main character of a comic strip

should not be too much of a showboat.

He also once said

he wished he could use Charlie Brown—

whom he described as

the lead character every good strip needs,

“somebody that you like that

holds things together”—a little more.

But he was smitten with Snoopy.

(During one of the Christmas ice shows

in Santa Rosa, while watching Snoopy skate,

Schulz leaned over and remarked to

his friend Lynn Johnston, another cartoonist,

“Just think … there was a time when

there was no Snoopy!”)

Schulz, Johnston writes in an introduction to

one of the Fantagraphics volumes,

found his winning self in this dog:

Snoopy was the one

through which he soared.

Snoopy allowed him to be

spontaneous, slapstick,

silly, and wild.

Snoopy was rhythm, comedy,

glamour, and style …

As Snoopy,

he had no failures,

no losses, no flaws …

Snoopy had friends and

admirers all over the globe.

Snoopy was the polar opposite of

Charlie Brown, who had nothing but

failures, losses, and flaws.

But were the two quite so radically far apart?

Snoopy’s critics are wrong,

and so are readers who think that

Snoopy actually believes his self-delusions.

Snoopy may be shallow in his way,

but he’s also deep,

and in the end deeply alone,

as deeply alone as Charlie Brown is.

Grand though his flights are,

many of them end with his realizing that

he’s tired and cold and lonely and that

it’s suppertime.

As Schulz noted on The Today Show

when he announced his retirement,

in December 1999:

“Snoopy likes to think that

he’s this independent dog who

does all of these things and

leads his own life,

but he always makes sure that

he never gets too far from

that supper dish.”

He has animal needs,

and he knows it,

which makes him, in a word,

human.

Even Snoopy’s wildest daydreams

have a touch of pathos.

When he marches alone through

the trenches of World War I,

yes, of course, he is fantasizing,

but he also can be seen as

the bereft young Charles Schulz,

shipped off to war only days after

his mother died at the age of 50,

saying to him:

“Good-bye, Sparky.

We’ll probably never see each other again.”

The final comic strips,

which came out when

Schulz realized he was dying,

are pretty heartbreaking.

All of the characters seem to be

trying to say goodbye,

reaching for the solidarity that

has always eluded them.

Peppermint Patty,

standing in the rain

after a football game, says,

“Nobody shook hands and said,

‘Good game.’ ”

Sally shouts to her brother, Charlie Brown:

“Don’t you believe in brotherhood?!!”

Linus lets out a giant, boldface “SIGH!”

Lucy, leaning as ever on Schroeder’s piano,

says to him,

“Aren’t you going to thank me?”

But it’s Snoopy who is

grappling with the big questions,

the existential ones.

Indeed, by his thought balloons alone,

you might mistake him for Charlie Brown.

The strip dated January 15, 2000,

shows Snoopy on his doghouse.

“I’ve been very tense lately,”

Snoopy thinks,

rising up stiffly from his horizontal position.

“I find myself worrying about everything …

Take the Earth, for instance.”

He lies back down,

this time on his belly,

clutching his doghouse:

“Here we all are clinging helplessly to

this globe that is hurtling through space …”

Then he turns over onto his back:

“What if the wings fall off?”

Snoopy may have been delusional,

but in the end he knew very well that

everything could come tumbling down.

His very existence seems to be

a way of saying that no matter what

a person builds up for himself

inside or outside society,

everyone is basically alone

in it together.

By the way,

in the end Snoopy did admit to

at least one shortcoming, though

he claimed he wasn’t really to blame.

In the strip that ran on January 1, 2000,

drawn in shaky lines,

the kids are having a great snowball fight.

Snoopy sits on the sidelines,

struggling to get his paws around a snowball:

“Suddenly the dog realized that

his dad had never taught him

how to throw snowballs.”

written by SARAH BOXER

NOVEMBER 2015 ISSUE

The Atlantic